COMMENTARY

In the wake of Quran burnings, thoughts of prohibitions loom large. It is tempting to assume that it only concerns the overt narcissists and racists expressing their hatred towards Muslims. I can understand that sentiment. I might even sympathize.

I, too, am deeply troubled by the evident underlying hatred of figures like the Danish individual Rasmus Paludan.

However, each time I approach what we might term blasphemy laws, an internal image is ignited in my mind. It is from the documentary “Nothing Compares,” where the artist Sinéad O’Connor tears apart a photograph of the Pope during her performance on Saturday Night Live in 1992.

She protested, far ahead of her time, against the symptomatic abuses of the Catholic Church against children. Against religious oppression in Catholic Ireland.

I cannot quite let go of the story of how the world turned against her. The jeers and insults she endured. How she was ostracized as an artist.

Stand Up for O’Connor

I repeatedly come to the conclusion that, no matter how wrong and how much harm the racist Paludan— who should be held accountable for his incitement without necessarily invoking blasphemy—commits, society’s foremost principle must be to stand up for O’Connor.

That’s why I’ve been frustrated by how casually we, pressured into compliance by Turkey’s threat of withheld NATO membership against a government entirely lacking a backbone, are leaning towards a zeal for prohibition.

A march towards censorship. From the right to protest against oppression.

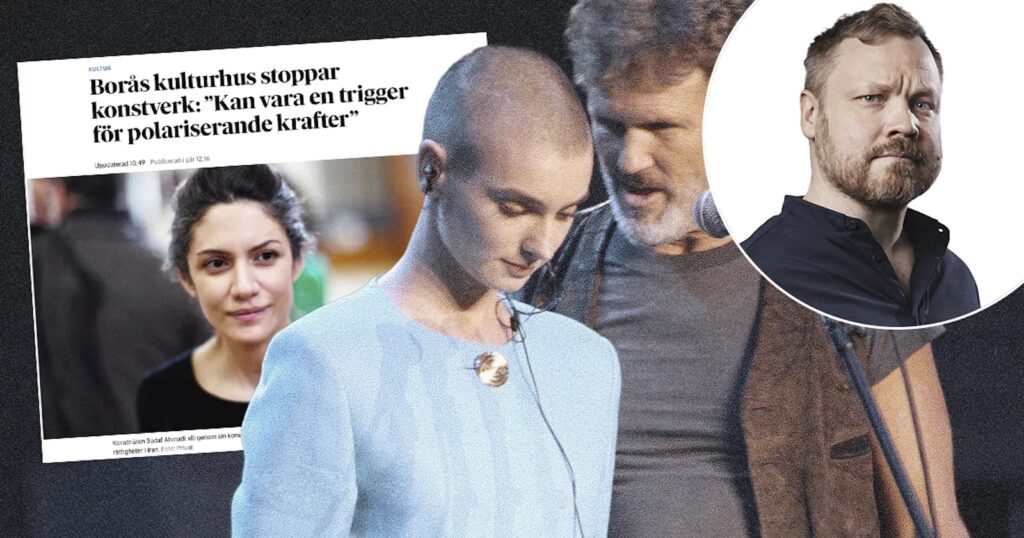

Removing Parts of “Concrete”

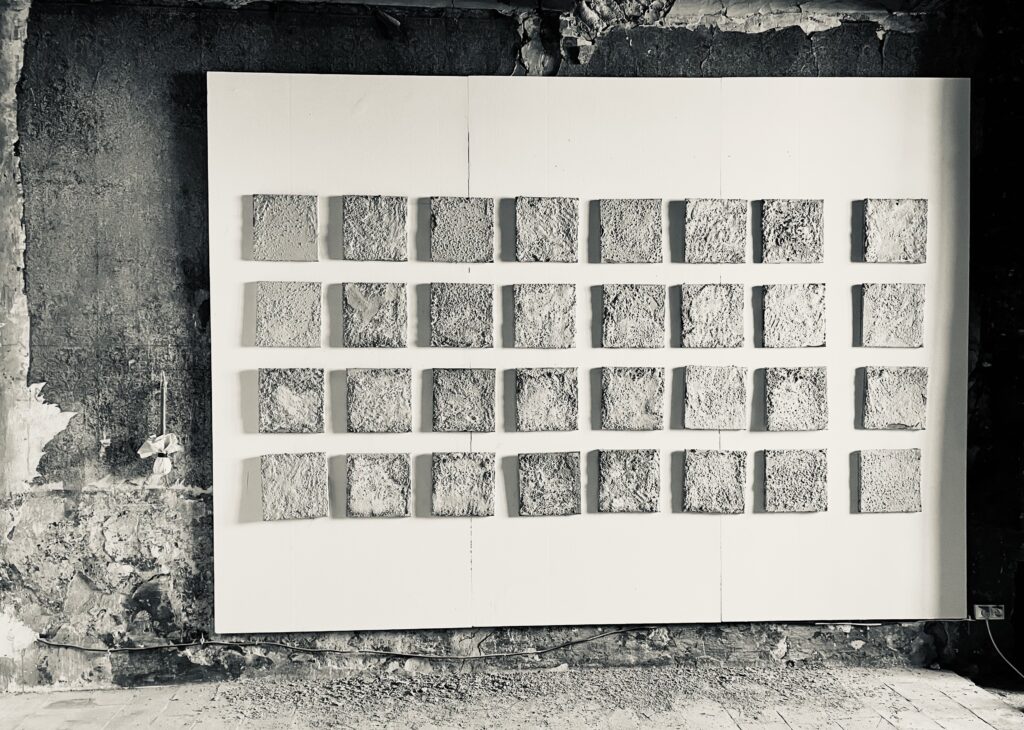

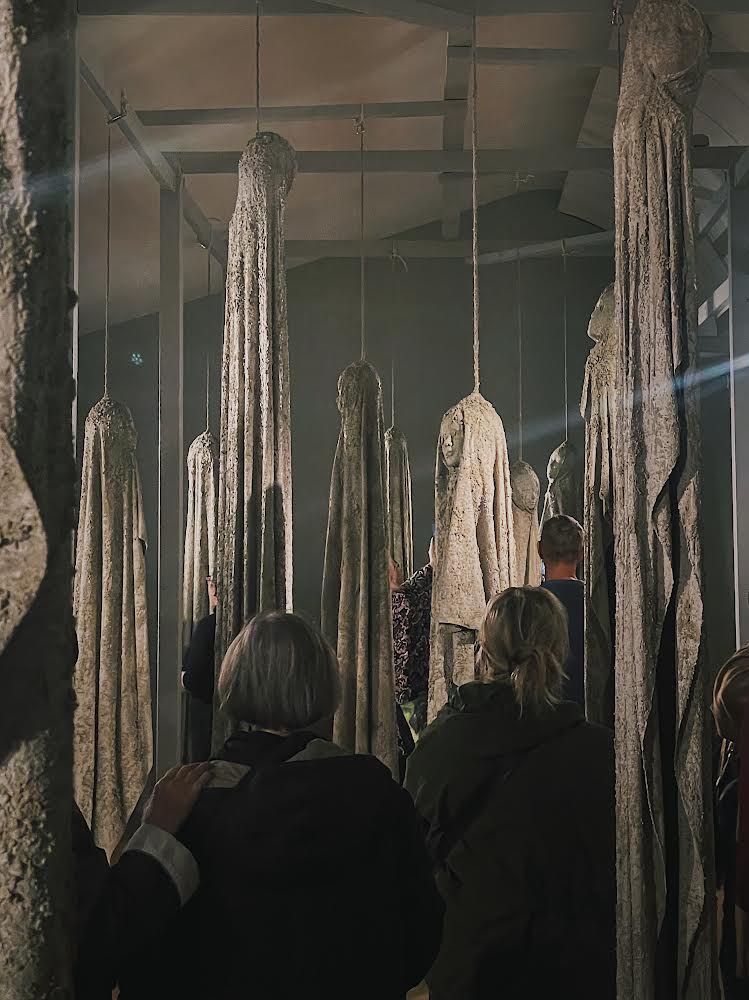

Yesterday, we received notice that Borås Cultural Center is removing parts of the exhibition “Concrete” by the Iranian artist Sadaf Ahmadi. The artist was raised in Tehran, and the cement objects depict veiled women.

The symbolism is as comprehensible as it is unprovocative. The cement embodies the weight of the veil.

Culture Chief Ida Buren refers to “security threats,” “Quran burnings,” and states that the decision was “very difficult.” It should not have been.

This is the consequence of an unholy union between Swedish nervous bureaucracy, a government willing to throw anything under the bus for NATO membership, a dominant Time Law party with fervent hatred towards Muslims, and raging theocracies, all seemingly getting what they desire.

Resistant voices are silenced. Those who scream the loudest win.

Pauldan took over the room

The consequence of the current discourse became exactly what worried me. Paludan took over the room—O’Connor was silenced. For that is the doomed reality.

The discussion about Borås Cultural Center is, in essence, a conversation about where the path leading to blasphemy laws takes us. My answer is that it leads straight to hell.

The application becomes blunt in its signals to society, where nervous culture chiefs shut down—yes, censor—art.

I guess both Richard Jomshof, the Iranian regime, and Erdogan applaud the result.