SETTING PROJECT

A Reflection on Childhood Encounters with Ideological Constraints

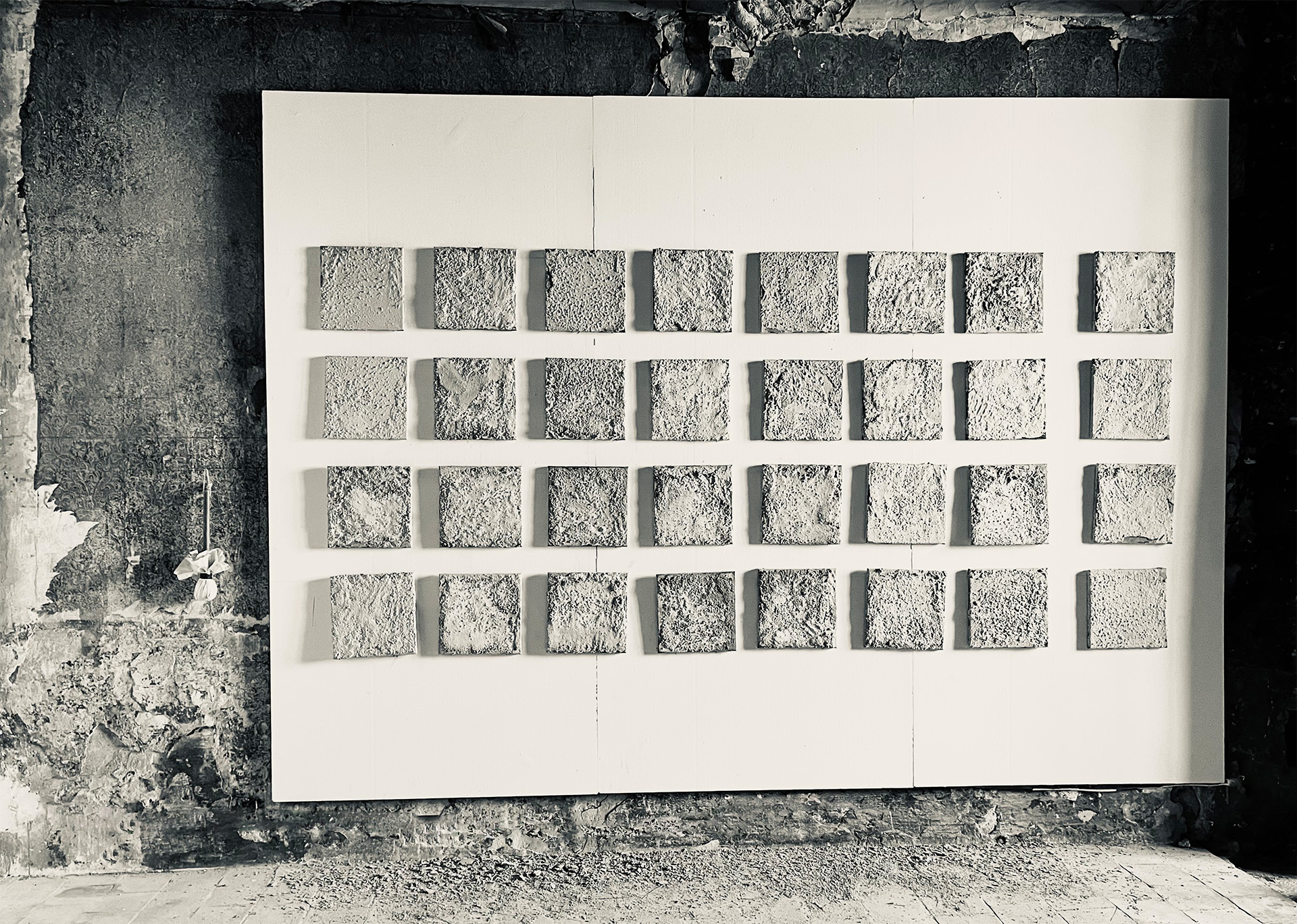

SETTING

This exhibition comprises ten meticulously crafted concrete mannequin heads adorned with long veil-like hijabs. This artistic installation serves as a poignant expression of my early encounters with the political dimensions of mandatory hijab enforcement during my formative years in the 1990s. At the tender age of twelve, I began to grapple with the religious and ideological impositions surrounding hijab, a transition typically experienced by girls as they approach adulthood, often around the age of nine. However, my journey into religious observance had commenced four years earlier when I and my friends found ourselves compelled to participate in daily school prayers and adhere to a litany of regulation.

During this period, I experienced a profound spiritual awakening, finding solace in my connection with Allah. This spiritual elevation was a shared experience among my close-knit circle of friends. Paradoxically, as I ascended spiritually, I found myself increasingly bound by a web of rules governing my attire and conduct. These regulations acted as constraints, limiting my freedom of movement and segregating me from my male peers and cousins. I became ensconced in an ideological cocoon, metaphorically encased in a heavy suit of armour, leading to a sense of spiritual stagnation. Consequently, my personal state of being seemed to mimic a state of lifelessness.

In my artistic work, I endeavour to articulate the demise of my inner self, an issue with profound humanitarian and child-centric dimensions. I assert that this pertains not to a critique of Islam as a faith but rather to an exploration of its politicisation. It is imperative that we differentiate between the two, lest we find ourselves mired in chaos. In tumultuous circumstances, fear often prevails, leading to decisions to censor art addressing pressing issues and critiques. Such decisions, I contend, are misguided and ultimately contribute to the problem at hand.

Sadaf Ahmadi