AFTONBLADET: "Borås Halts Artwork – for Security Reasons"

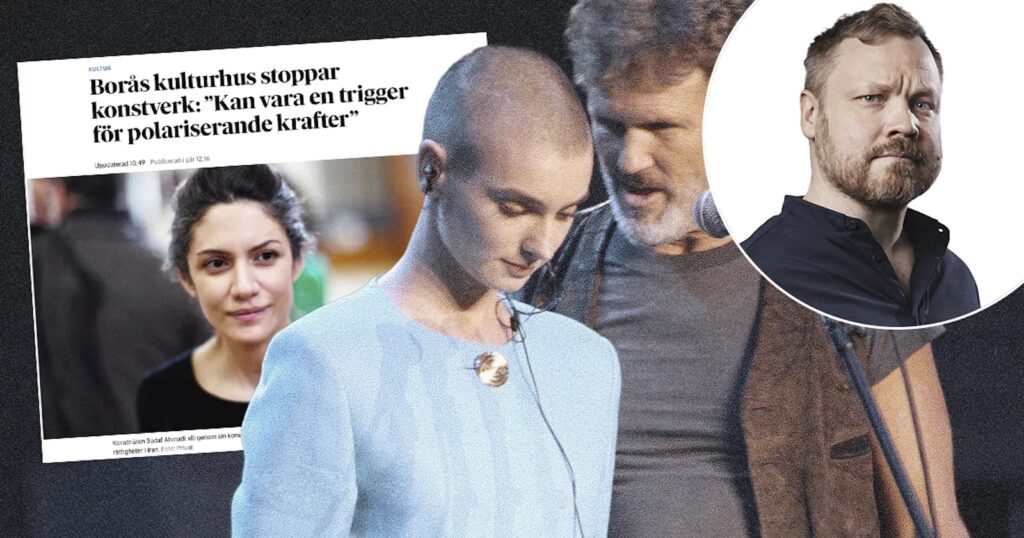

The artist Sadaf Ahmadi is critical of the decision.

“It sounds exactly like in Iran,” she says to Borås Tidning.”

Sadaf Ahmadi has previously exhibited her sculptures, depicting women in the Iranian full-body veil known as the chador, at various locations in France. However, in her hometown of Borås, the same exhibition has now been partially halted, citing reasons such as the Quran burnings and the potential for people to be offended, as reported by Borås Tidning.

“This feels like censorship, and it’s not the right way to handle these important issues,” says Sadaf Ahmadi to TT. “I see art as a way to shed light on the issue of women’s rights in Iran. When you censor it, isn’t the same thing happening as in Iran?”

Opening on Anniversary

One part of the exhibition, a series of portraits of individuals who have died in connection with protests for women’s rights in Iran, will be displayed in the cultural center starting on September 16 as planned. This date marks the anniversary of the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Zhina Amini in Iran last year.

However, the concrete sculptures have been stopped.

Ida Burén, the cultural chief in the city of Borås, notes that the security-political situation has changed since the initiative for the exhibition was taken.

“It has been a very difficult decision to make considering the role of art and culture in society. However, it is a comprehensive assessment, which also involves the placement of the artwork in our cultural center, an open space where all residents of Borås can enter,” says Ida Burén.

“If it had been exhibited in the art museum, the issue could have been handled in a completely different way. Now I had to make a comprehensive assessment based on the fact that it is precisely in our open cultural center.”

TT: How do you view the perception that this might be seen as censoring an artist who wants to use her freedom of expression to criticise the regime in Iran?

“I can understand that, with Sadaf’s history and background, I understand her perspective on the matter. It is a dilemma as a cultural chief to have to make this decision. However, it is a risk assessment that has been made.”